The Englishman highlights an intriguing story in Time, in which the magazine accuses the French of no longer being able to lay claim to much in the way of culture, indeed that French culture is as good as dead. It has provoked predictably outraged howls of protest in France itself.

But this pained reaction also points up one of the more unusual aspects of the French psyche: that the French need constant reassurance that their cultural contributions to the world – in fact their contributions to the world, full stop – are as remarkable as they assert. There is a curious insecurity, almost a neurosis, at work here and I have never entirely understood why.

America aside, there is practically no country in the world that can legitimately claim to have had a more sustained and deep-rooted cultural impact on the modern world than France. Modern art, to take merely one example, is to all intents and purposes a French invention. Fashion, film, philosophy and literature all bear a similarly clear French imprint. Moreover, is there any country where the arts of civilised living have been raised to a higher pitch? And this is as true of urban life (the banlieus aside) as it is of rural life.

Could anyone other than the French have come up with champagne? Or cognac, come to that?

Of course, the country has enormous natural advantages: a vast coastline (crucial in the pre-aviation age in giving access to the wider world), a climate that is near consistently benign and a huge range of landscapes. It is also the only European country that is both northern and Mediterranean. Plus, at least in European terms, it is very large. (There is an interesting aside here: ask any Frenchman or woman which is the largest country in western Europe and I guarantee they will say Germany. The actual answer, needless to say, is France.)

That it has exploited this head start to the full is equally incontrovertible. To a significant degree, the appeal of France is precisely its heady mix of landscapes that seem to have been precisely created as a backdrop to a cultural richness that, while part of a wider European whole, is nonetheless distinctively and unmistakably French. So why are they so touchy about it? What's the problem?

If there is an answer it is chiefly a combination of fear of, and resentment towards, the Anglo-Saxon world, which for the French means a malign mixture of Britain and the United States. Anglo-French military rivalry, which lasted from the 100 Years' War to Waterloo, may have ended with the defeat of Napoleon but in every other field, above all the competing claims of industry and the scramble for empire, the rivalry endured and endures, despite, possibly because of, the EU.

America presents a different problem. On the one hand, France's role in helping to secure American independence, however much this stemmed at least as much from the desire to do down Britain as to extend liberty to a nascent United States, remains a source of justified pride. It equally underlines how much ideals of modern liberty owe to 18th-century France, for all that the country's absolutist monarchy was anything but a friend to liberty so far as the king's own subjects were concerned.

Yet on the other hand, France's attitude to America is notoriously snooty, with the country widely dismissed as crassly commercial and, isolated pockets aside, astoundingly unsophisticated, at any rate in French terms.

There is considerable resentment at work here, of course. For one thing, the French have never quite forgiven the Americans for liberating them from the Nazis – Britain of course also falls into this category, albeit on a smaller scale. Much more importantly, however, they can't allow themselves to acknowledge America's global cultural hegemony, to say nothing of its financial and military clout, roles which in a properly ordered French world would be the exclusive preserve of France itself.

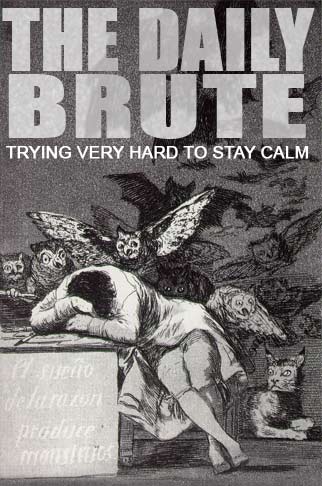

That France should be sucked into America's dumbed down world, in which practically every sense of what is fitting is overturned; that, worse still, the French language should have to cede primacy to English; and that, ultimately, there is nothing that can be done to reverse this inexorable cultural take-over are matters to have even the most sanguine members of Academie Francaise stamping their feet in fist-clenching fits of impotent rage.

But interestingly this chip on the shoulder does not extend to what might most properly be thought the real Anglo-Saxon world, to wit Germany. On the face of it, this seems strange given that three times in 70 years France was invaded by Germany, twice being defeated while its only victory, in the First World War, was arguably Phyrric at best. How else to regard the deaths of 1.4 millon Frenchmen? It was also of course hugely dependent on Britain and, in the end, America. On the other hand, Germany post-1945, ruined and prostrate, was clearly very different from the aggressively expansionist Germany of the years between 1870 and 1945. There is much truth in the celebrated claim that, for France, the fundamental impetus behind the EU is a French jockey on a German horse.

But this still doesn't entirely explain why the French should be so defensive about their cultural impact or so quick to take offence when it is questioned – or at least when they think it is being questioned. After all, the Italians don't seem to feel the need to bridle in the same way. True, Italy has never had designs on global hegemony. Further, by at least the mid-18th century, what in the Middle Ages had been an economic and political powerhouse had subsided into an economic basket case thrown back on tourism and able only to point to past glories. So perhaps they have just had longer to come to terms with their reduced status.

But I still find it odd that a country with so much to boast about should continually feel the need to do so.

I suspect I am going to have to return to this subject. After all, there is the small matter of whether or not Time's provocative claim is right.

3 comments:

If you want a really good argument with a patriotic Frenchman, try pointing out (as I sometimes do) that the French Revolution was a total failure. Basically it overthrew an absolute Monarch, spent a decade or so up to its knees in blood, and then was itself replaced by another absolute Monarchy. Oh and it was such an utter bloodbath that it killed the nascent republicanism across Europe stone dead for at least a century.

To cut a very, very long story short, I both agree and disagree. Yes, by 1815 the French were back where they started, albeit via an emperorship, ie, they swapped an absolute monarch for an absolute emperor, though equally the French attitude to Napoleon is intensely ambivalent, his empire flaring up and then shrivelling in a matter of only years (though of course he also introduced a series of exceedingly important and long-lasting administrative reforms in between the fighting). There are then further revolutions in 1830 and 1848 before, in 1852 a second empire is declared which in 1870 collapses in ruin and defeat and the Commune.

In other words, from 1789 to 1871, there are 82 years of political turmoil. So much for the Frog Revolution.

On the other hand, whatever the bloodletting of the Commune, it did at least lead to the Third Republic which, shaky or not, at least endured until 1947, surviving the trauma of WW1 as well as the political instability of the 30s. It was also properly democratic.

So whatever the lasting political instability introduced by the Revolution you can argue that, even if it took 82 years, it did eventually produced a much more stable and much more fair society.

I think it is also important to remember that, however different the practice may have been from the theory, that same theory – in essence, Libertie, Egalitie, Fraternitie – was and is extraordinarily influential.

That said, part of the resentment the French feel towards le monde Anglo-Saxon is precisely its political stability compared to their political instabilty.

There was of course also the more or less disastrous 4th Republic. And I think it is fair to count 1968, too, as a further example of this underlying fragility.

But it is a HUGE subject.

Slightly OT: What I find astounding is the lack of history and understanding that French people know about their own country. Many under the age of 30 no nothing about such poignant events as the Prussian siege of Paris, Pétain's contribution to WWI, Franco-Belgian occupation of the Ruhr etc. I think they've been truly EU-washed and brought up with a sanitized version of history which spouts longstanding Franco-German cooperation, but breaks the World Wars down to pure aberrations of political climate, often due to external influences: WWI - Aspiring empires of Western powers; Nazism - reaction to hyper-inflation etc. The fact they've been fighting each other time immemorial doesn't come into it...

That said, one could say the same of the UK's population under 30 also. However, the difference in the teachings of history over here is that these days we're made to remember all the bad and none of the good. Vice-versa for France.

Post a Comment